Plus, guests: Vince Gill on acoustic guitar, lovely scatting by Diane Schuur, great vocals from newgrass singer John Cowan, and in the coda, sustained rock guitar shredding from Jim Oblon. “Better Times,” clocking in at 7:29, is a song of hope that begins quietly a cappella, growing to include a panoply of joyful instrumentation: New Orleans–style sax, clarinet, trombone, fiddle, and mandolin.

“That last guitar chord is the arc of COVID in my life: ‘Yeah, we’re good.’ ‘No, we’re not.’” “I really wanted to end it with ‘Better Times Will Come,’” she explains. The title track to The Light at the End of the Line, a goodbye song to fans, was “too hard” a way to end the album, she felt. In closing this chapter, she remains vigilant. Hence the divestment: Ian started Rude Girl Records in 1992, and to date, there are more than 25 Ian albums and tons of additional Ian footage under its auspices.

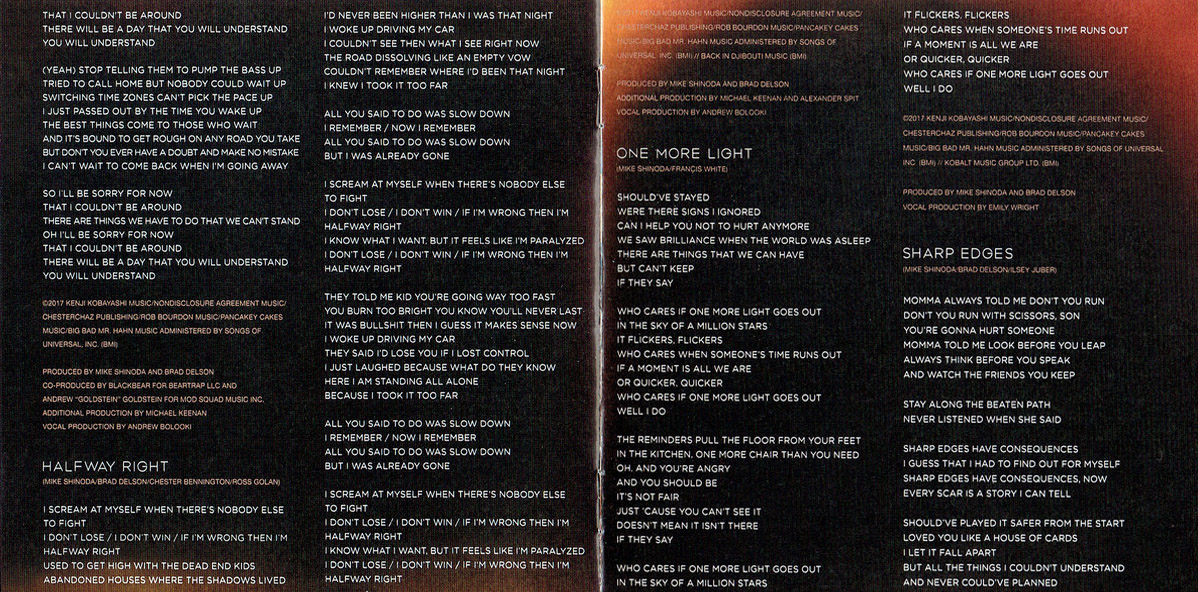

#ONE MORE LIGHT ALBUM SINGS FOR FREE#

“You’re selling out for free time, because that’s about the only thing that money can buy you. But as a socially conscious activist whose new song “Resist” addresses female genital mutilation, among other long-standing outrages, don’t think she’s “selling out.”

So, along with her final album, Ian’s master tapes and publishing rights are up for sale. So for me, the only way to get back to my work is to say I’m done. But also just the sheer amount of work it takes to protect it, to shut down people who are misusing it making T-shirts, putting on plays, whatever. “What they don’t see in ownership is not just the terrible responsibility that comes with it-because to me, it’s a terrifying responsibility. Of course, some artists do less, but Ian simply can’t. When I walk out onstage, nobody’s supposed to know that I’ve been at that venue since two o’clock, that I’ve spent five hours already on the show. Performers, Ian believes, are “supposed to be magic. I’m tired of business,” she states.Ĭaring deeply can be exhausting. I’ve watched it grow from being a business to an industry. I’ve been self-managed now for going on 20 years. “I’ve been in the music business since I was 12, 13. Ian is vibrant, in a life filled with non-musical endeavors that include journalism, a science fiction anthology (she’s been a rabid fan of the genre since she was young), and more-rather than “retire,” she prefers “rewire.” From her sunny home on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where she lives with her wife of 19 years, Ian is equally bright and open, over-ear headphones and a ready smile in place for a day of remote interviews.įrankly, though, she is tired. Her career as a recording artist-which includes perhaps the truest lyrics ever about the agonizing emotions felt by high school girls, in 1975’s “At Seventeen”-is coming to an end via the aptly titled 12-song album The Light at the End of the Line. And then I would have had a whole different career. Knocked out by the Jersey girl’s bold songwriting maturity and bell-clear voice, on 1967’s CBS documentary Special Report: Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, Bernstein called her a “great creature.” Laughing on our Zoom call, Ian notes, “That’s followed me the rest of my life,” adding, “But without him, I doubt that ‘Society’s Child’ would have happened. “Society’s Child”-a poignant tale of interracial love, with lyrics including, “Why don’t you stick to your own kind? / Preachers of equality / Think they believe it?”-found early support from conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein. A preternatural talent changed that trajectory, and by age 15, in 1966, she’d released a song that remains a landmark of musical social commentary. And I was going to do music on the side,” says Janis Ian, chuckling at her youthful career aspirations. I was gonna be a veterinarian, and lifeguard in the summer.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)